you'll note the following maps:

it would follow relatively clearly that israel is targeting the shia regions, which makes sense because hezbollah and iran are both shia groups (hamas is sunni).

that is important in how i frame this.

i've stated something like this previously: i'm going to support israel's actions on the basis that it could lead to the liberation of lebanon. what am i talking about?

the left (or what i call the fake left) has recently become the stupid party, which is frustrating. it is very common amongst leftists on the street to talk about jewish or christian colonialism in the levant and support for hezbollah or hamas as resistance groups struggling against colonialism. comparisons to the crusades (which they don't understand at all and which most of them know of solely through monty python) are frequent. they often embarrass themselves.

i am not a conservative, i am a hard left socialist. i want to apply my engels correctly, here, and avoid making the mistakes that are endemic on the fake left. i would argue that if you do this correctly, you realize that hezbollah is a colonial movement that is colonizing lebanon with shia muslim settlers on the direction of iranian imperialism. it follows that if you want to have a true anti-colonial narrative, you support the jews pushing the shia back, and opening space back up for the christians and the druze, who are the indigenous groups.

lebanon is very old, but it has only been called lebanon (after the hebrew word for a mountain) recently. very far back in history, lebanon was the centre of the civilization that the greeks called phoenician and who called themselves canaanites. these people were not arabs and did not speak arabic, they were basically jews and basically spoke hebrew.

these three language groups at the bottom of the tree - hebrew, phoenecian and moabite - correspond to modern israelis (and many palestinians who were jews before they converted to islam), lebanese and jordanians.

it is not clear what religious views the ancient hebrews had, but they were probably similar to the phoenecians and these three groups would have, at the time, formed a cultural continuity called "canaan". the canaanite people and their north african colony in carthage were systematically erased from history by the roman senate at the conclusion of the punic wars; valuable practical information was converted to latin and the rest of it was erased, burned, destroyed and forgotten. our knowledge of this region's history is consequently more sparse than it should be.

the old testament is a work of fiction written in babylon by captured hebrew slaves, but the archaeology does uphold two key ideas: (1) that the assyrians burnt everything down c. 700 ce and took the survivors back to mesopotamia as slaves and that (2) when the persians conquered the babylonians (who had since overthrown the assyrians), they did so with a level of strong philphoenecianism and a desire to rebuild canaanite civilization. i have never seen it suggested that the sort of mysterious origins of the persian empire (the history we have records a personal conflict and is probably a legend written by greeks) have to do with the collapse of canaan cutting off trade networks into the iranian plateau, but it's a good theory in the framework of a marxist filter on history. that is, the iranians may have taken down the babylonians with the intent to rebuild the ports on the coast in the first place. secular and mythological history records a figure named cyrus who conquered most of the middle east, freed the jews and rebuilt the phoenecian port cities in lebanon with the motives of rebuilding the phoenecian trade networks and building a navy to conquer europe with.

the ancient persians are themselves more obscure than they ought to be because the muslims tended to prefer greek sources and systematically destroyed ancient iranian culture and written iranian history. iran, itself, is a victim of arab colonization, and they know it.

this is a map of persian administrative divisions before alexander and is where real history really starts.

the three provinces of yehud, samaria and phoenecia were hebrew or canaanite speaking, while eber nari spoke aramaic and became aramea. the people in the province of arabia were not what we call modern arabs (who at the time lived on the red sea coast and south towards yemen). the region is called edom in early sources and contained in the canaanite cultural sphere. the region, like other canaanite regions, eventually began speaking aramaic. there's some curious evidence that they worshiped zeus; the region may have been mostly greek, following the bronze age collapse (well before alexander).

these new jews that came into the region with cyrus were certainly monotheistic and were very heavily influenced by the persian religion of zoroastrianism. like the druze thousands of years later, post-captivity judaism is actually a syncretic religion with a very heavy indo-european influence. unlike islam as it developed centuries later, judaism is not at all similar to indigenous semitic religion and has almost no lingering semitic cultural references (like a moon based calendar) besides some myths recorded in the old testament, like the the story of isaac and abraham, which was clearly intended to teach the idiots to stop sacrificing their kids to baal. broadly speaking, judaism is an overwhelmingly iranian religion and these new jews that came into the region (after the assyrians burnt it to the ground) seem to have at least intermingled heavily with the persians while they were in slavery and may have been an entirely introduced ethnic group altogether.

aramaic became one of the four official languages of achaemenid persia, which was famously conquered by alexander the great and split up amongst his generals. the levant was where they all met, and the place they fought wars in. further, the indigenous armenians and iranians (under the parthian tribe rather than the persian tribe) eventually won independence and came in and out of the levant. when the dust of the collapse of the persian empire, and subsequent reforming under the parthians, settles and when the military influence of greek rule is replaced with the cultural hegemony of hellenism, there is actually a hellenized independent jewish state in the region that speaks greek and aramaic and does not include phoenecia, which remains a part of seleucid syria:

this gets absorbed into rome in a way that splits phoenecia off into syria more or less permanently.

it is still true under trajan, at rome's greatest extent.

however, in 135 ce, the emperor hadrian absorbed the province of judea into syria to create syria-palestina, thereby cancelling the jews and replacing them with the philistines and completing the dream of cato. the philistines were not arabs but were a greek group that had migrated into the region c. 1500 bce. well, that's what you get for pissing the romans off. that was, like, 300 years previously.

constantine reunited the empire and converted it to christianity but it split into a tetrachy again when he died and was permanently partitioned in 395.

you'll note that the diocese of egypt was split from the diocese of oriens (both in the prefecture of the east), meaning the oriens is now composed of syria and arabia (including palestine/judea and phoenecia).

this is a zoom in to the map at 395 showing the diocese of the oriens.

the empire then began to reorganize into "patriarchates" run by church despots and a number of "heresies" began to develop. in europe, the primary heresy amongst germans was arianism, which insisted that jesus was a man and not a god. the extent to which these arians were christians at all or if this was just an excuse for roman history to gloss over the non-christianity of the german tribes is an open question, but the issue played a primary role in the conflict between latins and germans, which collapsed the roman empire and eventually resurrected into the reformation (it never really went away. the reformation was fundamentally a part of the long war between germany and italy). in the east, they had the opposite heresy, called monophysitism, which claimed jesus was not a man but was only a god. this was popular amongst semites and i'm pointing to it because it became a key factor in the inability of constantinople to hold the east in later centuries. in both cases, people have a problem with the contradiction - the double think - that jesus can be a a man and a god at the same time. it didn't fly in either direction, it seems. a lot of people died over this bullshit.

the next thing that happens is that the arabs conquer the region in the 7th century, and islam very quickly became the dominant religion in the former persian empire but it took a very long time for that to happen in the former roman diocese of the oriens (syria, palestine/judea and egypt) and large christian populations also continued to exist in the battleground region of mesopotamia for many centuries after the initial violent arab onslaught. the romans held on to asia minor for quite a long time and periodically reconquered parts of the levant, including all of lebanon and a good percentage of israel, but they couldn't hold it permanently:

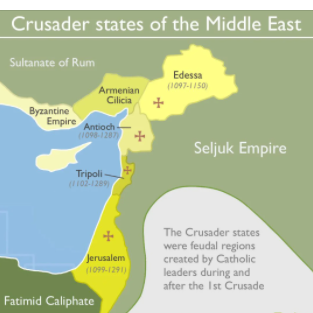

the romans lost the mediterranean coast, which was then conquered by the seljuks, who had since taken over persia. this is leading into the first crusade, which was intended to liberate the region on behalf of the romans, but the crusaders instead set up germanic warrior-king states that were initially well received by the indigenous christian groups but quickly wore out their welcome; while these crusader states in some cases survived for centuries, they were all eventually reconquered by reinvading muslims from the south or east, who in time began working together (indeed, a consequence of the crusades was that the muslims reunited to reconquer the region, while the christians couldn't help but foolishly fight each other, instead).

the reason the crusaders were successful in liberating and holding the area in the short run is that the region was actually majority christian. the crusades were a corrupt disaster run by barbarians, but the basic crux of their purpose - to liberate christian indigenous groups suffering under tyrannical imperial muslim rule - is basically true. if they hadn't been corrupt despots that the indigenous christians grew to despise for their own poor rule, the crusaders may have held the area permanently, as they did have majority support to begin with.

as it is, a result of the crusades is that the christians in the broader middle east began to be colonized. that hadn't been the case before the crusades, for the simple reason that the christians were the overwhelming majority and the muslims were the overwhelming minority. islamic history (which is mostly fictional narratives and silly stories. like the guy that swam across the mediterranean to start a dynasty in spain. right. lol.) glosses over this, but the reality is that the early muslim states in these regions were military dictatorships with a small number of muslims ruling over a christian supermajority. if the muslim ruling clique had gotten too pushy with the christians, the christians would have overthrown them, and they eventually did.

when did these areas in the old diocese of the orien convert to islam?

This combination of factors meant that the Middle East became predominantly Muslim far later than an older generation of scholars once assumed. Although we lack reliable demographic data from the pre-modern period with which we could make precise estimates (such as censuses or tax registers), historians surmise that Syria-Palestine crossed the threshold of a Muslim demographic majority in the 12th century, while Egypt may have passed this benchmark even later, possibly in the 14th. What we mean by the “Islamic world” thus takes on new meaning: Muslims were the undisputed rulers of the Middle East from the seventh century onward, but they presided over a mixed society in which they were often dramatically outnumbered by non-Muslims.

to this day, there's a large coptic christian minority in egypt that identifies itself as the indigenous group in egypt. the indigenous groups in syria and armenia are also christian, but they were almost entirely wiped out by a series of genocides by the turks in the 20th century.

what made lebanon different than anywhere else in the middle east until recently is that it remained a majority christian region all the way from the arab conquest in the 7th century until the 1970s, which is why it was turned into it's own country by the french mandate following the dissolution of the ottoman empire in 1918. otherwise, it would have remained a part of syria, as it always had been. lebanon has been called the principality of beirut (the city was probably built by the phoenicians, rebuilt by the persians, conquered by the greeks and romans, converted to christianity, conquered by the arabs, conquered by the turks, fought over in the crusades and then conquered by the french) and been a part of the province of syria since not long after the crusades, when the ottomons turks (in constantinople) conquered it from the mamluk turks (in alexandria):

(1) a large influx of palestinian refugees, who are muslims, and are mostly converted jews, with some minor admixture from introduced arabs.

(2) christian lebanese migration out of lebanon, especially during the civil war. these are also descended from the canaanites/phonecians/hebrews, with less arab admixture (and more persian, greek and roman admixture).

(3) iranian shi'ite colonization, especially in the south.

the result has been an intentional attempt to ethnically cleanse the region of the indigenous christian population and replace it with introduced muslim groups, in a process of purposeful colonization. the colonizing muslims are increasing their population through migration and high population replacement and the indigenous christians are losing population share through low population growth and emigration, as they are being intentionally chased out, and they are voluntarily leaving for europe or north america (which they perceive as more like them than the arab middle east). hezbollah, specifically, has been a brutally vicious imperial occupying and colonizing force, and has for several decades been attempting to enforce it's religious laws on the indigenous people in an extra-legal manner, including via capital punishment and torture. there have been uprisings against hezbollah in recent years, but the indigenous christians are frustratingly passive. and they just keep leaving instead of fighting.

i've pointed out already in this space that the lebanese have to fight back if they want to win and they don't want to do that so they're not going to.

however, what i want to see happen is for israel to try to rectify some of the demographic changes that have been happening, to push hezbollah out and to give the indigenous lebanese a chance to defend themselves or even to voluntarily choose protection by israel. the jews should get this without explaining it to them. they might not take the chance and israel needs to adjust it's messaging but i think this can be a just war worth supporting if it leads to lebanese self-determination in the end.

for now, if israel keeps targeting the shia regions, and keeps pushing hezbollah out of the region, i'm tentatively in favour of it.

(note: like much of my writing in recent years, this has been vandalized by some muslim revisionists and needs to be redone to reintegrate specific sections that muslims find offensive, but are historically and factually true and important to understand in order to get a good grasp of the history, whether they are offended by this or not.)